100 Years Of Adidas: The Making Of A Sports & Fashion Icon

Adidas has long been the nerdy kid standing in the shadows of the cool jock that is Nike. Certainly, although Adidas is much older -2024 marks the 100th anniversary of brothers Rudolf and Adolf ‘Adi’ Dassler starting to work together on their family shoe business – Nike has long been the champion, always ahead of the German brand in sales and, it so often seems, kudos.

Nike, it might appear, has come to embody the spirit of the rebel start-up – even while being a multi-billion dollar monolith – while Adidas was the corporate, suit-wearing stiff.

This, after all, was the company that thought it was a good idea to name shoe styles ‘Nora’ or ‘Jeans’. The company which turned down the technology that subsequently turned into Nike’s iconic Air unit. The company that wouldn’t match Nike’s offer to Michael Jordan – who wanted to sign with Adidas – and so lost out on the sponsorship deal of the century. Hell, Adidas didn’t even know about its cult status among the fledgling hip-hop community until Run-DMC’s manager persuaded one its executives to attend one of their gigs, and found a sea of ‘three stripes’ in the crowd.

Adidas didn’t realise how popular it was in the hip-hop community until an executive attended a Run DMC gig

While Nike made superstars of its designers, Adidas’ were mostly anonymous backroom boys. ‘Impossible Is Nothing’ is a good slogan, but ‘Just Do It!’ it isn’t.

Peter Moore and Rob Strasser maybe had the same impression once: that Adidas was never quite up there. Until that is, the Nike design and marketing bigwigs left the company to join Adidas, much to Phil Knight’s fury. Strasser came up with the idea of relaunching Adidas’ back catalogue as Originals, together with its mothballed Trefoil logo, even if it did take a decade for the company to actually do it. It was also Strasser who pointedly moved Adidas’ US headquarters to Portland, Oregon, down the road from Nike’s.

Rob Strasser moved Adidas’ headquarters to Oregon in a direct shot at Nike

But a deep dive into Adidas’s archives had him reeling. “I suddenly realised that, with the exception of the waffle trainer and that air bag [Nike’s Air Max technology], this guy Adi was the father of 90% of the [sportswear] industry,” he would say. Maybe Kanye West came to the same conclusion after leaving Nike too. His next stop would be Adidas, where, by the admission of the then-president of Adidas North America, Mark King, his collaboration “definitely helped make Adidas cool again”.

Indeed, it was Adi Dassler – from which comes ‘Adidas’ – who pioneered the idea of designing shoes to be functional for specific sports: he set out on the path that would lead to the modern track shoe, the modern football boot (and, for that matter, the modern football), along with shoes specially designed for every marginal sport from handball to high jump, boxing to fencing.

Sure, Nike has long dominated golf, tennis and basketball – a sport Adidas was the market leader in before Nike came along. But it’s precisely that focus which, arguably, has meant the latter’s back catalogue of styles is comparatively limited to endless reinterpretations of the Air Force 1, Dunk or Jordan.

Kanye has been credited with making Adidas ‘cool’ via his Yeezy line

In contrast, Adidas’ approach has not only tied it to sporting legends as diverse as James Hunt, Muhammad Ali and Gerd Muller, but given it a long roster of stone-cold trainer classics: the Gazelle and the Samba, the Superstar and the Campus, the ZX line and the NMD, even the Adilette shower slides, which sparked their own odd-ball, wear-them-out-with-socks fashion moment.

Then, of course, there is the Stan Smith tennis shoe – still Adidas’s best-selling style, 60 years old in 2023 and arguably the progenitor of today’s long line of stripped-back, luxury sneaker makers, reinventing the sports shoe as something semi-formal.

The Stan Smith is still Adidas’ best selling model and has influenced a generation of minimalist sneakers

In technology, for every Air or Zoom or Flyknit, Adidas has its Bounce, Boost, Torsion or Primeknit. And with its latest generation of products is pushing shoes with 3D-printed midsoles and uppers made by robots from TPU-coated yarns set at specific angles calculated by some heavyweight computing. ‘Vorsprung durch technik’ as fellow German company Audi once advertised. Performance products still account for around three-quarters of Adidas’ sales.

Yet for all that sports shoes are created first and foremost for sport, it’s their lifestyle resonance – on the street, in fashion – that arguably really matters, and which so often leads sneakerheads to fall into one or the other camp: you wear Nike, or you wear Adidas. Again, although Nike tends to dominate the collectables and resale sneaker market – and it should be credited with turning its cultish Jordan sub-brand into one that, alone, has been bigger than Adidas for much of its history – Adidas’ cultural cachet runs very deep, even if it’s not well known.

Adidas’ sponsorship of Run-DMC in 1986 may have been the first collaboration between the music and sportswear industries. It set the template for the endless collaborations that have followed and, to boot, made a style icon of the synthetic tracksuit, an Adidas invention. But the decade before that Adidas could claim to be the choice of none less than David Bowie, Jim Morrison and Bob Marley, as well as The Ramones and The Sex Pistols.

The Adidas Spezial line has long been a core part of football casual fashion

In the UK of the late 1970s and early 1980s Adidas was especially beloved, with both Acid House and the Casuals style subculture again making it their brand of choice. And not because they had been marketed to. “When I was buying into Adidas as a youth we were buying our trainers from shops that sold tennis rackets, cricket bats and air rifles,” says Gary Aspden, long-time brand consultant to Adidas and curator of its Spezial line. “We were actually taking something [we loved], adapting it and changing the context of it. Our shoes were really important to us.”

And so Adidas would continue to suggest credibility and authenticity with the most unlikely of clans. Come the late 1980s and into the 1990s, the US’ Nu-Metal scene had the likes of Korn singing ‘A.D.I.D.A.S’ and Limp Bizkit making Adidas the brand of its fan base, such that critics referred to their type of music as ‘Adidas Rock’.

In the UK, Jamiroquai’s Jay K would become an unofficial brand ambassador, such was his Adidas obsession, while Adidas was the shoe of Britpop and the confected rivalry between Oasis and Blur. Blur’s 1999 album ’13’ includes the song ‘Trimm Trabb’, named after one of the brand’s more esoteric styles.

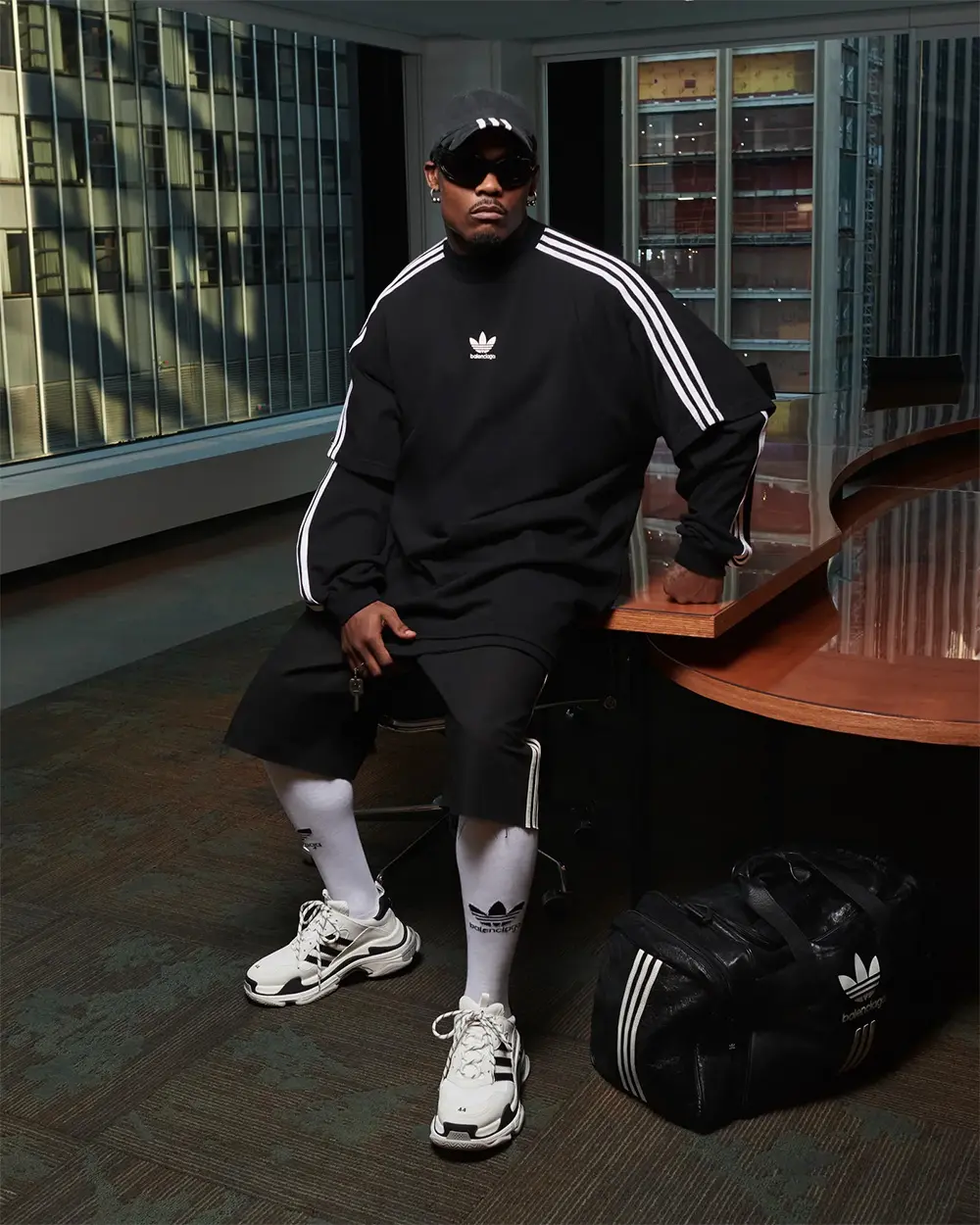

Adidas has collaborated with some of fashion’s heavy hitters, including Balenciaga

Nike fans might attempt to make a case for a comparable influence on culture. But there’s one way in which Adidas unarguably leaves it in the dust: its relationship with high fashion. While Adidas, like Nike, has released several tie-ins with important niche fashion brands and cult designers – A Bathing Ape, Craig Green, Fear of God, Palace, Moncler, Wales Bonner et al. – it has also collaborated with several major league names, including the likes of Balenciaga, Raf Simons, Rick Owens, Gucci, Prada and Stella McCartney.

But then, in 2003, Adidas’s most unlikely pairing came with the avant-garde Japanese designer Yohji Yamamoto. The resulting Y-3 line, which in time would lead to the creation of an entirely new division for Adidas – Sports Style, alongside Performance and Originals – would, it’s not too bold to claim, reshape fashion entirely.

Adidas’ Y-3 line changed fashion forever and invented a new genre of clothing

Launched a decade before athleisure went mainstream, Y-3 opened the portal for a more direct relationship between high fashion and sportswear that many other companies would later capitalise on. As Yamamoto pointed out, consumers were already looking not to fashion designers for inspiration but to athletes and rock stars. Put simply, in the words of Yamamoto, “we created something that did not exist before”.

Sometimes Adidas has got it right, and very right indeed. If it had turned down Michael Jordan, it wasn’t going to miss an opportunity like that again. This time it would be Nike that dropped the ball. Yamamoto approached Nike with his proposal first. “Their answer was very sharp and straight: ‘No, no, no. We will never make that [kind of clothing]. We are doing only sportswear’,” as Yamamoto would recall. “So I made a call to Adidas. And immediately they said yes.”